All about the equine foot

Posted 21st May 2020

We’ve heard the old adage “no foot, no horse”, but how can you keep this important structure safe? Holly Johnson explains

Horses have evolved to walk around on the equivalent of human fingertips or toes. This means that during fast work or high-speed exercise, when tremendous amounts of force transfer through each leg, the equine foot absorbs a lot of shock in its work to propel him forward.

One of the most important equine structures for the competition and leisure horse alike, it’s inevitable that, from time to time, things go wrong. However, by learning how the foot is put together, you’ll gain a far better understanding of how problems might arise and how best to prevent them in the future.

Did you know? The equine foot supports the weight of anywhere up to around 1,000kg of bodyweight, with weight distributed between fore and hind limbs at a 60:40 ratio.

Hoof anatomy 101

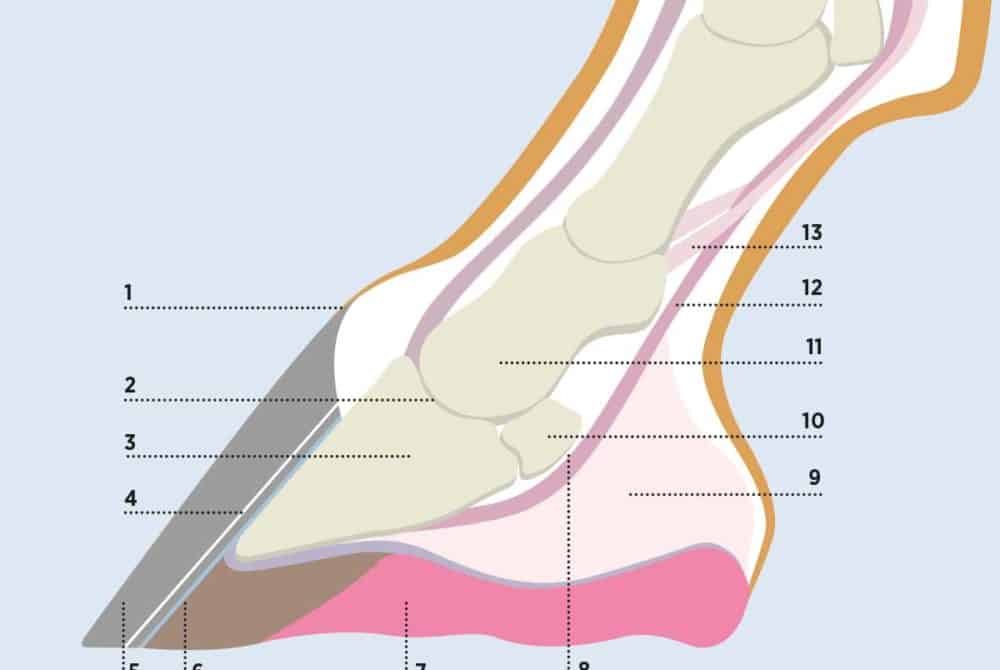

To appreciate what could go wrong in our horse’s hooves, we should first look at the structures inside them to gain a better understanding of their anatomy.

- Coronary band

This is where the hoof horn grows from. The periople is the new, soft horn next to the coronary band, which hardens to form the hoof wall.

- Coffin joint

A fluid-filled space between the pedal bone and short pastern that provides lubrication for the bones to move within the joint.

- Coffin bone (distal phalanx)

The largest bone within the foot. It’s crescent shaped and helps distribute the weight from the limb evenly across the sole of the foot. The wings of the pedal bone are the sections that extend on either side towards the back of the foot.

- White line

This is the junction that connects the hoof wall with the sole. It’s a weak point, and infection tracking up the white line can result in an abscess.

- Hoof

A horny capsule that protects the inner structures of the foot. It has no blood supply or nerves and grows continuously from the coronet towards the floor. A full hoof capsule takes around a year to grow from coronet to sole.

- Laminae

This consists of two layers – the epidermal layer attached to the inside of the hoof wall, and the dermal layer attached to the outside of the pedal bone. The layers connect in a similar way to Velcro, keeping the bones inside the hoof in a fixed position. Failure of this mechanism results in pedal bone movement in laminitics.

For more information about the equine hoof, pick up your copy of July Horse&Rider out now