A better understanding of how your spine works and how you can keep it healthy will pay dividends to your riding. Physiotherapist Nell Mead explains more

Our expert: Nell Mead is a physiotherapist who previously worked within the armed forces, but in 2010 founded her own clinic, Victory Health and Performance. Over the past decade, Nell has helped thousands of people back to health and mobility and is trusted by some of the world’s best athletes and performers. Nell looks at the whole body irrespective of where the symptoms are, understanding that everything in your body is connected.

Many riders suffer from back issues – not only from the rigours of riding, but from working on the yard and even previous accidents. Add to the mix that many of us also have desk jobs and are now having to work from home, with perhaps not the best home office situation, and it’s easy to see how your spinal health can deteriorate.

So, do you have to accept back pain as an inevitable outcome if you’re to continue with the sport you love? Or are there steps you can take that might ease the burden your spine takes every day? Luckily, there’s plenty you can do to ensure you keep your back in good health – a little work now will certainly make a huge difference to your riding and comfort in the long run.

Back to basics

Your spine is an incredible piece of living machinery, and it looks like an S-shaped column of alternating vertebrae and discs. At the front of the spine are the vertebral bodies – the bony building blocks of the spine – stacked between discs, which act as shock absorbers. It’s this front part of the spine that’s designed to take load. The discs are tough, rubbery cylinders with a liquid gel centre – a little like a jam doughnut. The jam’s filled with proteoglycans. They attract water, which is how the centre stays in a liquid form.

How it all works

When a disc is healthy, there’s plenty of liquid in its nucleus or centre. This liquid nucleus is the load-bearing part of the disc. The outer wall, or annulus, is much harder, but instead of being designed to bear load, it controls stretch. So, when your disc is working optimally, the nucleus stops the disc being squashed flat, and the annulus prevents it from being pulled apart.

It’s vital that liquid flows in and out of the nucleus. Like every other tissue in the body, the nucleus is a live structure, so it needs nutrients to flow in and waste products to flow out in liquid form. This process is much slower for discs than other tissues, such as muscles or organs, because the annulus is so dense and tough, making it hard for the liquid to find a path through.

However, the metabolic process – liquid nutrients in, liquid waste out – is significantly affected by our behaviour. When we sit down or stand upright for long periods, gravity begins to squash the discs and force liquid waste out. Conversely, when we lie down or stretch, this allows the liquid nutrients to flow in. This is why we’re shorter when we go to bed than when we get up in the morning – our discs tend to be progressively squashed throughout the day and then plump up again when we’re asleep.

When things go wrong

Problems arise when the amount of liquid flowing out of the disc exceeds the amount flowing in, causing the discs to dehydrate and stiffen. Spinal segments – each one consisting of a vertebra and the disc that sits on top of it – are barely viable at the best of times, because the journey that fluid and nutrients have to take, from the edge of the disc to the nucleus and back again, is so arduous.

The potential obstacles to the nutrients reaching the nucleus and waste products then being expelled include…

- unremitting spinal compression This might include staying in one position for too long or carrying a heavy load for a prolonged period of time

- core weakness Lack of strength in your abdominal muscles allows for uneven compression of the spinal segments

- chronic protective muscle spasm Common as a result of pain, this is your body’s way of trying to prevent further injury to already damaged tissues

- injury A fall, for example, can cause a traumatic rupture of the vertebral endplate, which is a thin layer of porous bone that attaches to the vertebrae

The problem in all of these scenarios is that the disc becomes compressed and is then prevented from stretching out again. Therefore, it’s unable to suck in fluid and nutrients to replace the fluid that’s been lost. Unhelpfully, when this happens the nucleus stops producing proteoglycans as efficiently, meaning it stops attracting as much water, causing the disc to become dehydrated and flatten. In turn, the spinal joints then become stiff, which is the point at which you’re likely to notice a problem, because stiff joints hurt when you try do to normal, everyday activities. Manual therapists, such as physiotherapists, can feel these stiff joints when we palpate your spine.

So, what can you do about it?

The good news is that – possibly with a bit of manual therapy and definitely a lot of home exercise – a stiff spinal segment is a reversible condition. That is, it’s possible to get the joints moving again, and thus promote better disc metabolism – it may, in some cases, even be possible for the discs to rehydrate.

Stretch it out

Stretching in the correct way is key to promoting healing, here are a few things to look out for…

- don’t stretch in an upright position Lying down, or even hanging upside down, is the most efficient way to stretch out the discs – but any movement is better than none

- get on the move Think of a disc as being like a sponge – if you put a sponge in water, it’ll eventually absorb it. But if you squeeze it repeatedly to get the air out, it’ll take on water much more quickly

- move individual joints first If you simply stretch the whole spine, then the healthy discs will stretch but the stiff ones won’t, so you need to make sure you’re getting to each joint. Big, full spine stretches and exercises – which are also necessary – will be much more effective once you’ve got the individual joints moving first

Finding the right exercises for you is key – here’s how…

- see a manual therapist, such as a physiotherapist. Many are currently offering video sessions while they can’t physically see patients, and that can be a great way to get started

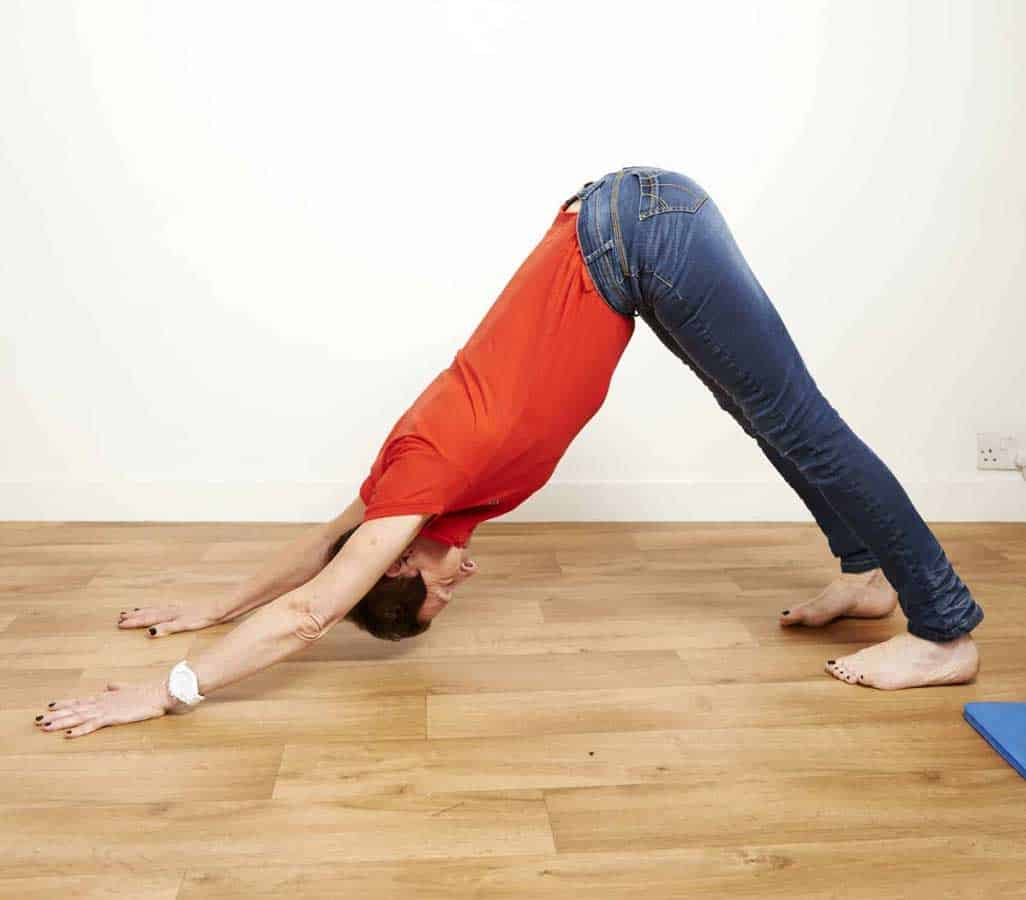

- big, yoga-inspired stretches to get your whole back working. You need to get both the front and the back of the discs stretched out, so good exercises will encourage flexion, such as touching your toes, and extension, such as the cobra pose or draping yourself backwards over a yoga brick or swiss ball

- Back In Action’s Mobiliser is a great piece of home kit that’s used by many riders. It’s designed to mobilise and stretch individual joints, and you can hire or buy one, or your therapist might have one in their clinic

- sit in something that moves, ideally a chair that allows for periods of back support and then lets it go unsupported for a while. Some people get on great with a rocking or kneeling chair, but I prefer to add a backrest or, even better, choose a chair like the Aculum – my favourite home office chair. This means you can switch in and out of activity even while you’re working

Bear in mind that, just as you wouldn’t try to run a marathon before your first 5k, if your back’s already feeling stiff or vulnerable, you may need to start with smaller movements before you tackle really dramatic ones. Don’t exercise into pain, and if you’ve got any concerns see a professional first – even during the lockdown, many physiotherapists are offering online assessment sessions to make sure you’re stretching safely.

And if you haven’t been able to ride your horse during lockdown, remember that when you first get back on your muscles won’t have been used for many weeks. So, take it easy and ensure you stretch and warm-up effectively beforehand, otherwise you may do yourself more harm than good – small steps!

For further information, or to seek individual advice from Nell, visit nellmead.com