Featured Professional

Carl Hester explains how to use advanced principles to improve your performance, whatever level you’re at

Half-pass, tempi changes, piaffe, passage, extended and collected gaits… skimming through the movements required in a Grand Prix test is pretty intimidating and alienating to most riders, and the seamless performances you see at the major competitions probably seem a million miles away from real life. But it doesn’t have to be this way – in fact, there’s a lot you can borrow from the top levels to use with your own horse and you can improve your own riding by watching, too.

TOP TIP – Don’t be intimidated or demotivated by watching top combinations. Instead, think about what elements you can apply to your own riding and your horse’s schooling level.

Watch and learn

To get the most out of watching upper level tests, you should identify the similarities between the level you’re riding at and the level you’re watching. There are some things common to every test, no matter what level, so don’t get hung up on the canter half-passes and tempi changes. Some of these common elements include…

- transitions Study how top-level combinations tackle transitions, both within the gaits and from one to another. There should be a noticeable gathering of power – much like what you need to feel when you’re working on your medium paces at Novice and Elementary, or when working on active transitions between the gaits at Prelim.

- straightness Watch how professional riders change their horses’ bend through movements such as flying changes – this will help to solidify the idea of having a moment of straightness in the middle of a movement, which will help you to perfect the serpentine that first appears at Prelim level.

- halts A square halt is a must at every level. Struggling to master the feeling of riding forward into the halt? Watch a top-level rider do it and you’ll see how they ask their horse to almost march in place. You’ll never ride a dressage test without at least one halt, so pay attention to this movement!

TOP TIP – The internet is a treasure trove of information, videos and resources that can help you improve your riding even when you’re out of the saddle. But take an educated approach and remember that anyone can post online, so seek out reputable sources.

Channelling the champions

Riding well is more about dedication, hard graft and physical fitness than it is about natural talent. To be successful at the top levels, riders need to be focused and precise. This means that they’re able to hold themselves accountable for every movement they and their horse make.

Do you know how many strides your horse does in 20 metres? I’ll hazard a guess that you don’t. But at the very top levels, where tiny discrepancies in accuracy can cost you the win, riders have to know exactly where their horses’ feet will land in any given movement. They will know that their horse puts six strides into 20 metres when travelling in a working canter and they know how many strides they’ll fit in if they ride an extension or a collection. These numbers vary from horse to horse and you can guarantee that top riders know them all. This means that if, for example, they have to perform a flying change over the centre line in a serpentine, they won’t have to guess the distance and risk overshooting it – they know that they’ll have to ask for the change on the fourth stride. This is a really achievable way for any rider at any level to improve their performance – all it takes is dedication and focus.

Exercises for all

The core principles of dressage are the same from Intro through to Grand Prix, so you may be pleasantly surprised to learn that top-level riders work on some exercises you’ll find very familiar. You can modify what the professionals do to reap the rewards of these exercises no matter what level you and your horse are working at.

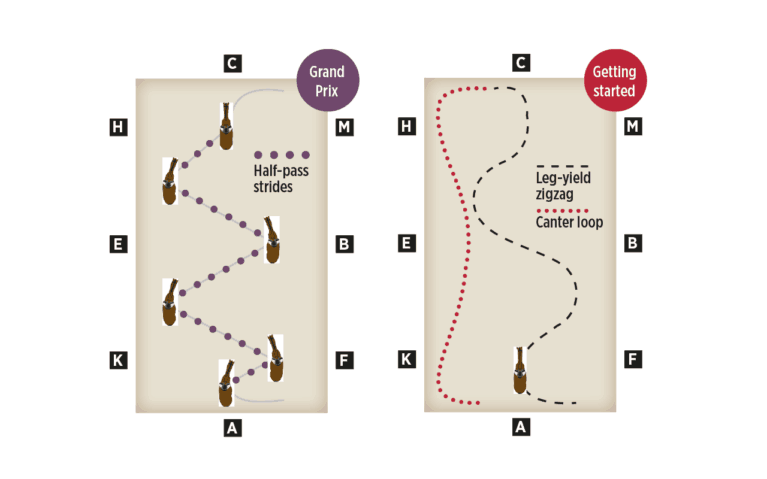

Lateral work

At Grand Prix, horse and rider are expected to perform half-pass zigzags in canter, with two three-stride half-passes and three six-stride half passes, punctuated by flying changes. That’s a lot of very advanced work, but don’t be put off. Instead, watch how these riders change their horse’s bend from one half-pass to the next and try to replicate that. You can use shallow canter loops down the long side of the school to practise moving your horse away from your leg without compromising his bend or ride leg-yield zigzags in trot to test your horse’s responsiveness.

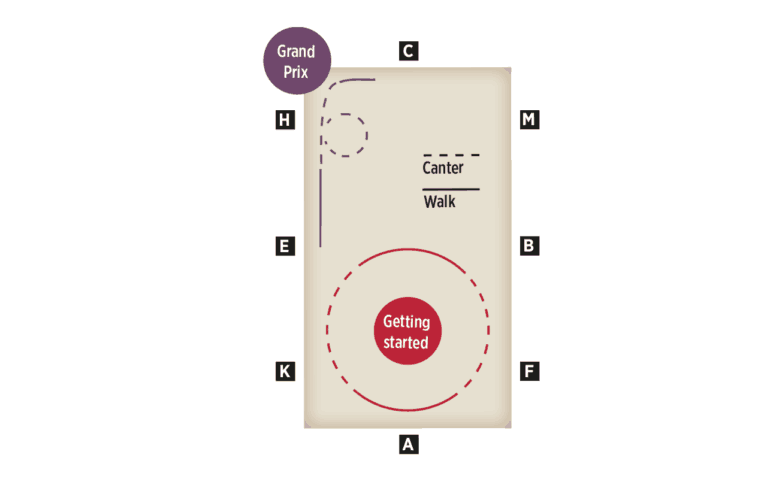

Transitions

Canter–walk–canter transitions are incredibly beneficial when ridden properly. For Grand Prix horses, they’re a great warm-up before moving onto very collected work like pirouettes, as they encourage the horse to use his entire body without punishing his joints. For your schooling sessions, you can use them to help your horse engage and bring his front end up. Just be sure not to ride them with a restrictive hand – the key is to maintain a tall upper body and stop the motion of your hips to help him drop down to a walk. If you watch an upper-level rider tackle this movement, you’ll notice that their horse almost seems to canter in place before the downwards transition.

TOP TIP – Once you feel as though you’ve mastered a movement, find a way to add another dimension of difficulty to it. Canter–walk–canter transitions too easy? Ride them in shoulder-in, or position them on a circle and ride each walk step in leg-yield or half-pass, slowly spiralling the circle in and out.

Talent spotting

Because my goal for my horses is always Grand Prix, I’m often asked at what point I know whether a horse will have the aptitude for it. The honest answer is that it differs from horse to horse. Some are very obvious at a young age, but some don’t show potential until they reach eight or nine. What can happen, though, is that I end up keeping a tricky young horse because nobody wants to buy it. This is sometimes a blessing because it makes us persevere with the horse and, eventually, find a way through the problem. That longer-term approach is sometimes what a horse needs to bring out his innate talent.

TOP TIP – If you’re struggling through a rocky patch with your horse, speak to your instructor or, if you primarily ride alone, book a few lessons with a trainer. They’ll be able to help you figure out how to tackle the problem and whether the long, consistent approach is better or whether your horse needs a professional tune-up.

The international advantage

Success at any level comes from taking the time to get to know your horse’s strengths and weaknesses and working with him to help support him. This becomes particularly obvious at the upper levels, where horses tend to be very fit and fairly hot, and where the atmosphere at competitions can be electric. For those upper-level horses with a bit more spark, the big international shows are actually the easiest to settle into. We’re often on-site for several days, which allows us to work on arena familiarisation and gives the horses a chance to settle into their surroundings. For this reason, some horses only really begin to get the marks that they’re capable of once they start to contest these bigger shows.

However, a horse’s competition schedule can’t be tailored to only include the big away shows, so it’s important to know your horse and have a plan for how to get him settled and focused as quickly as possible. If I take a horse like Nip Tuck, who is incredibly sharp and spooky, to an atmospheric venue such as Olympia, I’ll need to spend plenty of time making him face his fears by standing in shoulder-in next to the scary spots. I know him well enough to know that if I do this on the right rein he’ll spin and run away, so I only do it to the left, and I may give him three 20-minute rides rather than a solid hour-long session.

Unlikely achievers

By the time a horse gets to the upper levels of dressage, his level of body control is so high that it can override many conformational faults. For example, a horse may be long-backed or ungainly when untacked, but if he’s been trained to sit down behind and carry himself properly, then these flaws won’t be noticeable under saddle. The moral of the story? As long as it doesn’t cause your horse any physical issues, don’t worry too much about less-than-perfect conformation. Correct training can override natural build.