Often viewed as a symptom of older age, learn more about the joint disease that affects much of the equine population in one way or another

A common ailment among elderly equines – although their younger counterparts have been known to suffer from it, too – arthritis refers to inflammation of a joint. While there are many causes, it’s usually due to chronic low-grade repetitive trauma (wear and tear), acute trauma or infection. In this feature, I’ll be talking about the most common type – the form of arthritis that occurs as a result of wear and tear, also known as degenerative joint disease.

The cycle

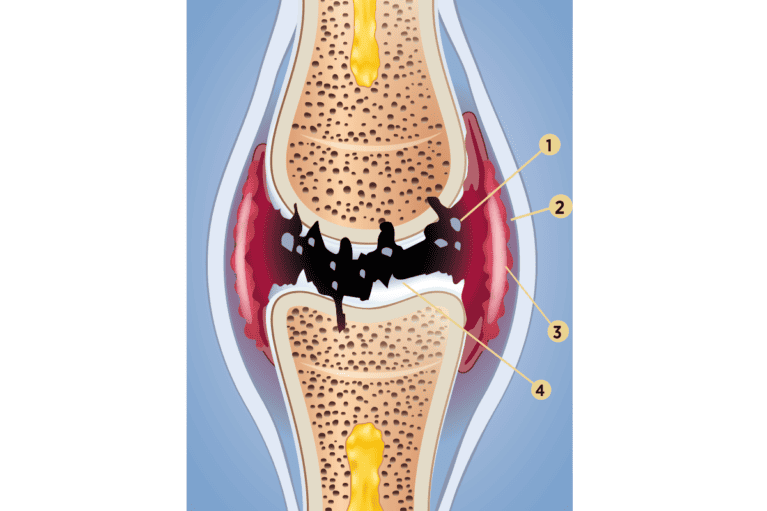

Degenerative joint disease can be the result of a major single event, or more commonly the outcome of ongoing low-grade repetitive micro trauma from exercise. Once the cartilage on the surface of the bone has been disrupted, the joint enters a vicious cycle of inflammation, an inability of joint cartilage to repair itself, then further degeneration that aggravates the inflammation.

Understanding the disease

Arthritis progresses because of the cartilage’s failure to heal and once damaged it’s either lost completely or replaced with lower quality material. In the simplest cases, arthritis involves the progressive deterioration of the cartilage and bone, but additional soft tissue structures, such as the joint capsule, tendons and ligaments, can also be involved.

Over time, arthritis produces lameness as the cartilage on the ends of the bones wears down. This may then lead to…

- excess fluid in the joint

- thickening of the joint capsule

- swelling

- heat

- pain

- restricted motion

- reduced performance

While any joint can be affected, different types of horses, or those competing in certain disciplines, might be more prone to arthritis in particular areas. Bone spavin, which affects the lower hock joints, and ringbone arthritis, which affects the pastern or coffin joints, are most commonly diagnosed in sport and leisure horses. Meanwhile, arthritis of the fetlocks and knees are more commonly seen in racehorses.

1. Cartilage fragments 2. Inflamed joint capsule 3. Inflamed synovial membrane 4. Destruction of cartilage

Prime candidates?

Osteoarthritis can occur in horses of all breeds, ages, types and levels. Although it’s most prevalent in older horses and those competing at levels of higher athletic demands, it can also be seen in very young animals and those carrying out less strenuous activities. There are other external factors that can contribute to arthritis, such as conformation, management, training level, footing and quality of farriery.

Symptom spotter

The symptoms of arthritis may develop subtly over time, going unnoticed by the owner in the earliest stages of disease. Some subtle signs that arthritis is developing may be a slight loss or decrease in performance, or perhaps the horse just hasn’t got the same vigour or interest for work. More obvious symptoms, or those noted in more advanced stages of the disease, could include…

- a loss of flexibility

- decreased range of motion of the joint

- stiffness

- lameness

- pain, heat and swelling in or around the joint – this is most easily identifiable in the lower limb

Arthritis found in joints affecting the horse’s neck or back may be more difficult for an owner to identify, but again is usually characterised by loss in performance and stiffness.

Lameness associated with degenerative joint disease usually presents as a horse who demonstrates initial stiffness under saddle, which gradually reduces with gentle work. An owner may note that the horse feels better when ridden directly out of the field or after time spent on a horse walker or walking to warm up.

Other conditions affecting the musculoskeletal system such as muscle stiffness, tendon and ligament injuries, or other sources of pain that may cause the horse to be reluctant to work may present in a similar fashion to arthritis. You should always consult your vet if your horse is showing symptoms like these.

Undergoing diagnostics

To be able to accurately diagnose a horse with degenerative joint disease, your vet will first conduct a thorough physical, clinical and dynamic examination. Depending on the outcome of these evaluations further diagnostics may be recommended. This could include nerve blocks using local anaesthetic around nerves or into joints to more accurately identify the origin of pain.

X-ray imaging is the most commonly used modality to visualise joint damage. This can show thinning of the joint space, new bone growth or spurs, demineralised bone, cysts, and information about the thickness or hardness of the bone lying beneath the cartilage. Additional imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, MRI or CT, may also be recommended and useful in clarifying the full extent of disease.

Treatment plan

To successfully treat joint disease, you’ll need to first achieve an accurate diagnosis. There are also additional factors – whether medical, competitive or financial – that may impact your options and these should be discussed with your vet.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of pain management. They’re effective, widely available and easy to administer. The most commonly used are…

- phenylbutazone (bute)

- suxibuzone

- meloxicam

- flunixin

- firocoxib

Bute is still usually the first choice and is widely thought to be the most potent for musculoskeletal pain. However, it can cause gastrointestinal irritation, inflammation, ulceration and potentially kidney disease (but this is unlikely in an otherwise healthy horse). Newer COX-2 selective NSAIDs, such as meloxicam and firocoxib, have no effect on the gastrointestinal tract making them safer for long-term use.

Systemically injected products like pentosan polysulfate, hyaluronic acid and polysulfated glycosaminoglycan are also used. These products may have an added benefit in managing joint disease from both a disease- and symptom-modifying standpoint, making them a reasonable part of a sport horse’s maintenance regime.

With a specific diagnosis, the most effective treatment may be joint injections. The most common are corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, polyacrylamide hydrogel and biologic therapies, which can be used individually or in combination as a course of treatments.

Corticosteroids are the go-to for medicating joints as they’re strong, effective and relatively inexpensive. Triamcinolone is most commonly used and unlike its predecessors, it’s been shown to protect cartilage and has a role in modifying the underlying disease, not only the symptoms. Care should be taken when using them if additional acute soft tissue injury has occurred as they may impair healing. Additionally, when considering an older or overweight horse who may be suffering from an underlying endocrine disorder, steroid use could increase the risk of developing laminitis.

Polyacrylamide hydrogel is a newer treatment that has been used in recent years with much success as a frontline treatment. It’s also effective in joints that have been unresponsive to or for horse who may not be a candidate for steroid use.

Biologic therapies (for example, IRAP, PRP, stem cells MSCs) are currently being studied and used more frequently in practice. Newer data on stem cell products produced specifically for use in the joint show that this treatment may halt or even reverse the deleterious effects on the joint cartilage. Additionally, biologic treatments may be a good substitute for corticosteroids in the case of a diseased joint with additional soft tissue injury where steroids would be contraindicated.

Supplements

Supplements are often used in an attempt to prevent joint disease or alleviate its side effects. There are many products on the market so it’s difficult to work out which ones are most or least effective. As with most things, it’s likely to be a case of you get what you pay for and the more expensive supplements may have more rigor behind them. There is limited scientific data supporting their use so, if in doubt, consult your vet to ask them for their recommendations.

Management options

Most treatments offered by your vet are directed to managing the arthritis rather than providing a cure. There are also management practices you can adopt at home to manage this condition. These include…

• weight It’s well known in humans and dogs that increased bodyweight has a negative effect on osteoarthritis, and every effort should be made to maintain a healthy weight

• activity Sedentary horses tend to be stiffer, and warm up more slowly into exercise. Therefore, access to regular turnout or turnout/walking prior to exercise can be very beneficial

• temperatures Cold temperatures can contribute to further stiffness and efforts to provide warmth and shelter

• exercise Encouraging consistent gentle exercise may also be preferential to no exercise at all. The benefit is particularly notable in sport horses who are happily maintained in a regular exercise routine, but following a holiday often return to work with much pain and difficulty

• physiotherapy This can be a useful addition to management of a horse with arthritis because joint disease can alter muscular function, fine movements and balance, and by improving these the affected joints will be better supported

Walk on water

Underwater treadmill exercise has been shown to improve the symmetry of muscle function, posture and balance, and it improves range of motion, too. There are different aims to water treadmill exercise – to decrease weight on the limbs a higher water level is used to increase buoyancy, in chronic cases showing a decreased range of motion the water level should be just above the affected joint to encourage a greater range of motion.

The bigger picture

As with all things in medicine, prevention is better than cure. That said, despite best care and management, it’s never possible to predict which individuals will develop arthritis or why. Diagnosis isn’t a retirement sentence, though, and owners should work as a team with their vet, farrier, instructor and chosen bodyworkers to come up with a realistic plan for the future.

Our expert – Rachel Read DVM CVA DACVSMR MRCVS is Clinical Director and the sports medicine specialist at Troytown Equine Hospital, Kildare, Ireland. She’s a specialist in equine sports medicine and rehabilitation. Her main clinical interests lie in poor performance investigations and orthopaedic sports injuries.