Most Read Articles

Monty Roberts, famously known as the man who listens to horses, talks to Georgia Guerin about his life and where it all started

In his 81 years, it seems that there’s not much Monty Roberts hasn’t done. He’s worked with more than 11,000 horses and in front of public audiences totalling three-and-a-half million people. He has his own TV series, is the author of a book that was on the New York Times’ best-seller list for 58 weeks and, he tells me, has more than 400,000 likes on Facebook. To top everything off, in 2011, Monty received a personal honour from Her Majesty the Queen, a Royal Victorian Order for services to her racing establishment. Behind the scenes, he also has a wife, three children and around 60 horses, has fostered 47 children and owns Flag Is Up Farms, where some of the world’s most successful performance and racehorses are started.

To explore this extraordinary career spanning more than six decades, we started at the beginning. Monty explained that horses were an integral part of his life from a very young age – his father was the manager at a large equestrian training facility in California. “It was a riding school, a training ground, a racetrack, everything rolled into one and, as far as I was concerned, everyone had horses.

“In 1939, when I was four, my father put me in a horse show and I won. But I was riding seven or eight hours a day and I was in a class with kids who rode for one hour a week at most, so it wasn’t really very fair. After that, I was taken on the road competing, because the more I won, the better it looked for the training centre.”

It all sounds like a child’s dream, but Monty’s story soon took a darker turn. “I lived in this idyllic world with my pony, Ginger, that any kid would just love. But on the other hand, my father was a very violent man, with horses and with me – he broke 72 bones in my body before I was 12. So I saw the world from two different sides all the time.” Monty didn’t go to school, but had teachers brought to him while he was on the road, and would go to school to take his exams. “I never knew another way of life and I feared my father fiercely. I didn’t know the feeling of stage fright. The audience was my friend, because he never beat me in front of an audience. I would migrate to an audience and I loved groups of people, lots of people. It was when there were no people that things weren’t so good.”

Life on the road wasn’t all about competing and Monty did some stunt work for movies, too. In the 1940s, many of the films shot were about a child and their horse, and Monty recalled a time, when he was eight, that his father got a call that said, ‘You have to come to northern California and bring that kid along, he’s got to do some cross-country jumping’. It was for the film National Velvet. The actress, 11-year-old Liz Taylor, had been filming some ridden scenes when she fell off and broke her ankle, so they needed a stunt double – Monty.

A pivotal point came early in Monty’s life, when he really turned against his father. “When I was seven, our equestrian facility was confiscated to house Japanese-Americans. My horse never showed up at the new place and I was told about a week later that my father had sent him to the butcher.” At first, Monty said he thought that he’d never ride another horse for as long as he lived, but then Brownie came along. “My father tied one of Brownie’s hind feet up and when I came down the next morning, Brownie was standing in his own blood. I took his foot down and got beaten badly for that.

“It was around this time, at seven years old, that I realised I had a way of doing things differently that I wanted to develop.” Monty told me the story of an unnamed mustang of his father’s who showed him that there was a communication system that he could use with horses. The mustang would respond to Monty’s actions in a way that let him know whether he was doing things right. “I thought, ‘What? Who’s going to apologise to this species? Somebody’s wrong here and I’ve got to show the world! This is incredible!’. My father told me it was rubbish and airy-fairy.”

Photo: Ele Milwright

Chasing championships

Monty rode to a high level in many different disciplines, including showjumping. He said that, at one point, he was obsessed with winning championships, but eventually specialised in western riding. “I came to hate everything people were doing with horses in other disciplines in the name of winning, but the western disciplines were going a kinder way.”

Was becoming a champion always Monty’s ultimate goal? It seems hard to believe that competing was just about the winning for him, and he explained that he thought that when he was winning world championships, everyone would see him and his way, and people would change. But it didn’t happen. “People don’t change that easily. In all fairness, an idea should have to jump through hoops before it’s accepted. Well, mine had been through every hoop you can imagine! I won’t live long enough to see the kind of change I’d like to see, but it has reached critical mass, where change will be inevitable, and it’s happening right now, as we speak. And the strongest change I see? Western has gone so far to the non-violent side and all while nobody was watching. It just happened.”

Monty has always been on a quest to improve, learn more and educate people, and despite his unconventional schooling as a child, he continued on to study animal and human behavioural sciences, earning himself two doctorates. “I wanted to learn why we do what we do, and why my father behaved the way he did. And I wanted to know why horses thought in their way, too.”

There were no courses in Monty’s methods, so he changed that with the help of Kelly Marks, who became the first instructor. “Now there are 70-odd of them around the world and it’s changing horsemanship. It needed changing, unless you believe that horsemanship has been okay for 6,000 years.”

The Queen’s influence

In 1989, Monty was talent-spotted by the Queen and, after he successfully worked with her horses, she sent him on a tour of 21 cities to spread his message. She also encouraged him to write a book – the best-selling, The Man Who Listens to Horses. “She said ‘This is the way, go ahead and turn it on its head, I want the world to know about it’. That really started to change it, because she had the influence.” Despite strong backing from the Queen, Monty explained that not all reaction was positive. He received threats of violence, and was called a liar and a fraud. Some claimed that his concepts were inhumane and a psychological trick that enslaves horses, which he strongly refutes.

“I don’t understand human beings at times. There are so many things that could be done to improve horses’ welfare that aren’t being done, but people put so much energy into trying to ban things. Instead, why not make it better? We’ve got to put horses first at some point. I have this obsession with making everything better and my critics keep me getting up every day to prove something. I think if they all went away it would be so easy that I’d quit trying. I’m 81 and I’m still trying, and with more success. They can begin to see, now, that I was right.”

How horses help people

As well as striving to help the world’s horses, Monty has branched out into improving the lives of people, too.

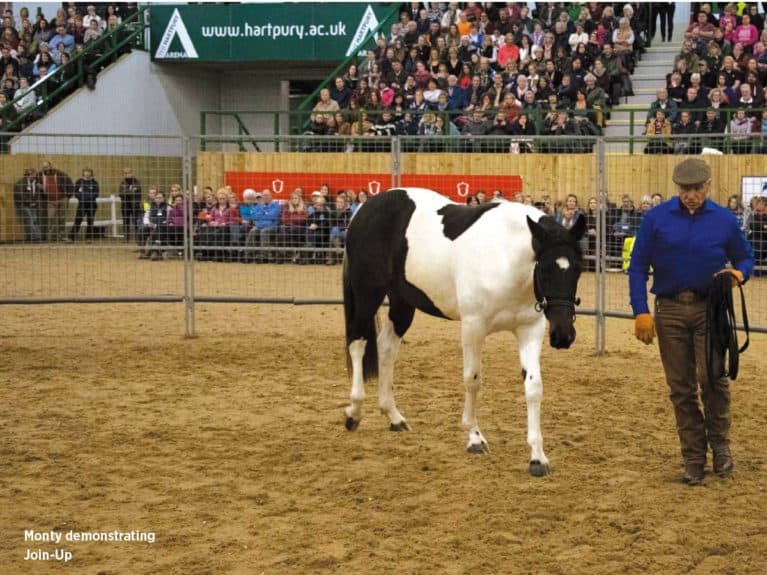

“Everyday someone says to me ‘you saved my life’ or ‘you saved my husband’s life’, or ‘you saved my wife’s life or my children’. I’ve discovered that horses have a capacity to really improve the mental capabilities of human beings, particularly in the areas of trust. People who have lost trust might commit suicide, take drugs or drink, and they need help to get back on the right path. All the veterans that come back from war, not just the ones diagnosed with post-traumatic stress, have trust issues.” Monty runs non-profit courses, where war veterans can experience the power of horses and his Join-Up technique, to combat this exact problem in the UK, Australia, the USA and Canada.

As horsey people, we all believe that horses are special. But for them to so successfully overcome negative attributes in people or really help them, there really must be something special about them. Monty explains: “Horses can’t lie. They act on the moment and can’t plan for tomorrow. They can remember yesterday, but only when it’s triggered by an action. They’re flight animals, which means they don’t kill any other species to live, so they want to be as far from violence as possible. So, as humans are predators, when a horse comes to you and wants to be with you, that’s got to be trust. They don’t just come by mistake, they have to consciously come to you.” Monty went on to explain that when a horse chooses to come to you, it helps the human brain deal with any anti-trust and innate fight feelings.

Monty’s famous technique, Join-Up, that he developed while watching wild horses as a child, is a crucial part of his work. Convinced there was a more effective and gentle method than traditional horse breaking, Monty developed Join-Up to end the cycle of violence that was typically accepted. The result is a willing partnership in which a horse can flourish rather than exist within the boundaries of obedience. He explained: “It’s hard to put it briefly, but let’s just say that, firstly, there’s no violence. Secondly, I call it Join-Up because you let the horses be themselves, free, but you can cause them, through their own communication system, to want to come to you rather than go away from you. If you can get them to want to come back to you, then you’ve been successful with Join-Up. When they come to you, good things happen, but when they go away from you, they go to work.” He refers to this as ‘picnic’ – Positive Instant Consequences, Negative Instant Consequences. If your horse gives you a negative act, there has to be a negative, but not violent, consequence. When he gives you a positive act, there has to be a positive consequence. He likened this to raising children or being a good partner, and said that when somebody does something that’s right, you have to tell them, because then they’re more likely to repeat it. If they do something wrong, they’ve got to pay a price for it. But the price is never violence.

Dealing with difficult horses

One of the more well-known branches of Monty’s career involves him working with other peoples’ horses. But, he went on to say, it’s often more about changing the people, rather than fixing their horses. “People bring their horses to me and they say, ‘My horse is naughty or he’s difficult, or he’s badly-behaved’. But none of them are naughty. Horses’ behaviour is a reflection of what humans have done to them, and some will be worse and more dangerous than others. They can’t lie, so they tell you exactly what’s happened. When I tell the owners that, often they say, ‘Oh, no, no’ and I know the truth straightaway!”

I asked Monty if any of this was frustrating and I completely understood when Monty said that he found showing an owner how to behave, but knowing it’s likely that they won’t continue this way, to be the most disheartening thing in his entire career. “If I work with 100 horses and their owners, 15 of them will be treated the way I tell them to and 85 of them will go back to square one within a few days or a few hours. It’s maddening, but it’s life. Maybe the 15 will tell 15 more and I just keep working.”

Monty believes that any normal person can achieve Join-Up, but some will do it better and some will take longer to learn. People with mental and physical disabilities, as well as children, have been very successful.

What’s really important

I wondered what part of Monty’s varied career he enjoyed most and thought that, perhaps, it might be a day off with his family. But he quickly cleared that up. “Day off? I had a day off, but I think it was nine years ago now, in Iceland. And then I got a call to go to California right away.” He compared my question to asking a parent who their favourite child is and couldn’t choose because every day is different. “I could easily say that it’s saving the life of one soldier, but I could also say that it was yesterday, working eight of the Queen’s young horses, too. They went from wild to friendly in a few minutes, which was a lot of fun. I don’t really see that much difference between the veteran or the child at risk, or the horse. All three would be very high on the list.”

Did this very busy man have any time to give his own horses? And did he form attachments with them like many other horse owners do, becoming a collector? He smiled: “I think I own about 60, but I’m not going to keep all of them for life. There are some who I’ll hold on to, though, and there has never been a point in my life where I’ve been without one of these special horses. There’s about as many of them as decades I have lived that were, or will be, my horse forever.” Monty talked about how each of these horses has taught him something in particular, but explained that other horses, who otherwise wouldn’t seem special, have taught him things, too. He spoke of a crooked-legged filly who belongs to the Queen: “She’ll probably never be anything special, except in this thing that she’s teaching me, which will influence and affect hundreds of horses after her.” And another horse, Prince of Darkness, a racehorse who was the inspiration for the creation of a protective blanket used in starting stalls, now used by thousands of racehorses across the world. “Every horse is important and you just have to look for that important feature. Each one has it, it’s just a matter of digging it out and then acting upon it – observation is the major thing. They all have a story for you. Each one helps me on my quest to leave the world a better place than I found it, for horses and for people, too.”

I asked him for a final thought – what did he really want people to know? Without hesitation, he responded: “Remove violence. Violence is never the answer.” And that really did round up everything he had to say, the foundation for his life’s work. It seemed an appropriate point to finish and, as I left, Monty added that he had a scheduled phone call with Her Majesty in an hour, before catching a flight to Johannesburg that evening. He really never stops.